In New York, burlesque meets the feminist struggle

“There’s not one type of sexy, and I think that’s an empowering thing to see people own whatever sexy is to them.”

brASS Burlesque, at the end of a performance

On a snowy pre-pandemic New York night, the backroom of Starr Bar in Brooklyn is hosting a burlesque show. Juniper Juicy, a go-go dancer with bright green hair and pointed faerie ears, who self-identify with the gender-neutral pronoun “they,” is allusively shaking their round buttocks, encouraging the audience to slip one-dollar bills in their fishnet stockings.

It’s the first act of Compost Bin!, a recurring performance by a troupe called brASS Burlesque – as in brown radical ass burlesque. The show’s description promises “liberation, justice, love” and freedom of expression for “people traditionally on the margins” and “queer people of color.”

The host of the show, Don DickRealis, a tall drag king with a purple Prince-like suit and thick black facial hair painted on a feminine chin, introduces the show as a “radical-ass political cabaret to deal with the world, because there is a lot of shit to compost.”

Don DickRealis is the drag king persona of female performer Aurora BoobRealis, known as Dawn Crandell in her everyday life. During the show, Don acts as a man, while seductively revealing a woman’s body, and then simulates intercourse with drag queen Munroe Lily. The gender confusion is of a piece with a show in which people undress, deploy glitter, and make strong political statements.

During the show its three creators, Dawn Crandell and the sisters Michi and Una Osato, stand on stage with a brown compost bin and asking the audience to shout names of things, so that they can be thrown into the bin, sprinkled with turquoise glitter and given back as empowering art during a future performance. Among the items listed by the audience are voters’ suppression, weak prosecution of cops, transphobia, and jails, cages and borders. Then, the three performers, with bare breasts and painted beards, dance to the sound of James Brown’s “It’s a Man’s World.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-r1xVDPI954

Burlesque and striptease are forms of entertainment historically popular among a male heterosexual audience. But in recent years, as sexual emancipation and LGBTQ+ visibility increases, women and people of all genders have taken up burlesque as a way to find greater self-expression. Burlesque performers and enthusiasts claim that shows like brASS Burlesque are a creative and powerful way to push back against patriarchal oppression and reclaim the narrative surrounding women’s bodies. Opponents say that, no matter the context, women stripping on stage will always be a perpetuation of the sexual objectification of women in society.

The debate is emblematic of a broader trend in feminism that sees the revival of sexual politics, of which the #MeToo movement is part. For example, Andrea Dworkin, an almost forgotten radical anti-pornography feminist who died in 2005 from a heart condition, has been rediscovered as an icon, and her insistence on women’s reclaiming ownership over their bodies is gaining new urgency. Similarly, the work of feminist performance artist Carolee Schneemann, who died in March 2019 of breast cancer and was largely ignored by the mainstream art world for decades, has attracted new recognition in the past few years.

With the exception of a period between the 70s and the 90s, when it faded into the underground world or largely blended in with mainstream striptease, burlesque has always been a place of pushback against conventional womanhood. It arrived in the US, in New York City, in 1868, with Lydia Thompson and her troupe, the British Blondes. Their performances presented the same draws that attract audiences today: a pushback against conventional womanhood and a redefinition of what woman and beauty is. Their shows, which were highly successful, featured classic art forms rewritten into satirical sketches delivered by curvaceous women in body-revealing clothes. It was a working-class form of entertainment, which mocked bourgeois standards and challenged the Victorian notion of the ideal woman as domestic, thin, and innocent. The British Blondes shocked and attracted crowds by being quite the opposite, displaying their voluptuous bodies on stage, being witty and cultured, dressing as men, and generally doing everything women were not supposed to do.

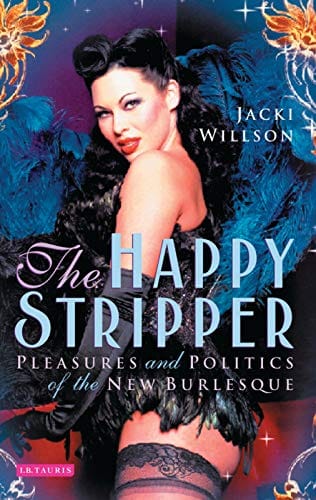

“By dressing in fetish, or dressing up as men or showing too much leg, they constantly pushed the boundaries of what beauty was, what women could be,” said Jacki Willson in a recent phone interview. She is a performance and culture fellow at the University of Leeds, where she teaches classes focusing on feminism and performance. She’s also the author of The Happy Stripper, one of the few academic books on burlesque. “There was a sense of it being a kind of testing ground for what’s sexuality, and how women could display themselves and display a kind of fluid sense of gender. So even from the start, I think, it was about what the category of woman is.”

Lately, a new interest in feminism and a resurgence of the discussion of what a woman can do with her body, whether it conforms to conventional beauty standards or not, is bringing burlesque out of the “demi-monde”, as Willson defines it, and into the spotlight. There is an upsurge of radical, politicized burlesque that embraces issues dear to contemporary or fourth-wave feminism, such as inclusivity and ownership of the female body.

“Burlesque [today] can include a 65- or 70-year old woman, it can include the tattooed woman, it can include fat women,” Willson said. “The other woman [compared] to what is idealized within the mainstream. The other, whether that be black, whether that be disabled, whether that be too tall, too short. Even the absolute idealized, but taking that far too far maybe, like for example Dita Von Teese.”

For Dawn Crandell, politicized performance is what brASS Burlesque is all about. “Audiences get excited by seeing different things,” she said during an interview, sipping tea on the couch of Bell’s Coffee and Design café in Soho. “You don’t want to see seven acts that are like, okay, boobs, yay, okay, you’ve just seen seven pairs of boobs. Like, what else do you have.”

Crandell, who’s 44 and describes herself as a “mom radical thinker,” came to burlesque the long way. She started performing as a stripper when she was 18 and a student at Sarah Lawrence, a small arts-oriented college north of New York City, because she needed money, because it was a punk rock thing to do, and because she liked to perform. But the hustling that goes along with mainstream stripping, getting the men to buy her drinks and give her money, wasn’t her forte. “I was never really good at that,” she said. “I just wanted to perform. I wanted to pick my songs, costumes. I just wanted to dance. And so even when I was a strip-club stripper, I realized [later], even if I had no idea what burlesque was, I was probably doing it.”

While she was pursuing an MFA in Interdisciplinary Arts at Goddard College with a focus on 20th century black radical artists, she started attending burlesque shows in New York and she liked them. “I was like, wow, this is all the good bits of stripping without the frustrating bits,” she said. “It’s all the things that I love, the costumes, the musicality, the telling stories with your body, without hustling and annoying costumers and all of the downsides of a strip-club, granted you don’t make as much money.”

What struck her, though, was the lack of diversity. “In two and a half years, I saw one brown woman on stage. And I was like, this is New York City, why, am I going to the wrong places? Like, are people who look like me not getting booked?” The result was an all-women-of-color troupe, Brown Girls Burlesque, which she co-founded in 2007 with Maya Haynes-Warren, and which was succeeded in 2015 by brASS Burlesque, which she co-founded with Una and Michi Osato, a threesome who describe themselves as “brown, queer, and femme.”

The idea behind brASS Burlesque is to create a space that welcomes all genders and people of color and puts on work that is difficult to bring to more traditional burlesque stages, either because it’s explicitly political, or because the performers are persons of color or queer or trans.

Crandell describes her core audience as “queer folks of color and their allies” and says they enjoy watching burlesque shows so much because they’re seeing something rare in [our] contemporary society.

“The burlesque that I like is not passive entertainment, it’s not like – I’m pretty and I’m here,” she said. “The burlesque that I’m interested in is saying something, is challenging you, like I’m going to be funny and sexy, I’m going to be really awkward and sexy.

“There’s not one type of sexy, and I think that’s an empowering thing to see people own whatever sexy is to them.”

In their effort to create an image of the sexual woman that is different from both conventional beauty ideals and traditional porn star clichés, burlesque shows like brASS Burlesque have much in common with 1960s and 70s feminists who sought to demystify sex and de-objectify the female body.

A recently rediscovered feminist performance artist is Carolee Schneeman, whose work was exhibited in a comprehensive retrospective last year at MoMA PS1. In 1965, Schneeman, posing as “image and image maker,” created the artistic film Fuses, in which she shows herself having sexual intercourse with her husband, thereby displaying her own female erotic gaze and at the same time being the object of the audience’s erotic gaze.

Hardly surprising, such activities were highly controversial and helped fuel a divide between what were known as sex-positive feminists and their opponents, known as anti-pornography feminists. To summarize a complex debate in a few words, sex-positive feminists saw such displays of female sexuality as an empowering way for women to take back control over their bodies and sexual narrative; by contrast, anti-pornography feminists saw it as a disempowering perpetuation of a patriarchal system, and a continuation – rather than a disruption – of the sexual objectification of the woman in society.

Such a debate, that came to the fore at the 1982, at a conference on sexuality held by Barnard College, continue to engage feminists today. After all, there is an inner contradiction in shows that claim to empower women but feature go-go dancers who ask strangers to put money in their fishnet stockings.

The National Center against Sexual Exploitation has inherited some of the battles fought by the anti-pornography movement during the so called “sex wars.” In a recent telephone interview, psychotherapist Mary Anne Layden director of the Sexual Trauma and Psychopathology Program at the University of Pennsylvania, made clear that, in her view, all acts that use a woman’s body to sexually arouse an audience are contributing to a crisis in sexual violence against women.

“We have massive, tsunami levels of sexual violence in our culture,” she said. “What is in the center of it? A belief that the whole point of women’s bodies is to sexually arouse men.” In her view, that belief fuels all violence against women, including rape and sex trafficking, and women stripping on stage, no matter the atmosphere of the club or the message behind the performance, are contributing to the belief that women’s bodies exist solely for male sexual entertainment.

“Now, they might want to send a different message,” she said. “But if people in the audience are getting the message that women’s bodies are the whole point of them, that’s not positive. It may in fact support sexism, it may in fact support sexual violence, it may in fact say that women’s talents are their breasts and buttocks.”

Every year the National Center against Sexual Exploitation publishes a Dirty Dozen List, in which it denounces organizations that promote sexual exploitation. The 2019 version includes Amazon, Netflix, and the entire state of Nevada, where prostitution is legal. But to Lynn Comella, associate professor of gender and sexuality at the University of Nevada and author Vibrator Nation: How Feminist Sex-Toy Stores Changed the Business of Pleasure, the ideology behind the list sees sex as something that is inherently dangerous.

“A lot of people just operate from panic, and fear, and misunderstanding around sex and sexuality,” she said in a telephone interview, rather than seeing that “female sexuality is both pleasurable and has some danger.” In her opinion, things such as burlesque striptease, feminist pornography or feminist sex-toy stores are not denying the reality of sexual violence. Rather, they are “cultural intervention” through which women are trying to create a different kind of sexual representation.

Michi Osato durante una performance (foto

d Eleonore Voisard @eleonore_voisard)

One of the acts of brASS Burlesque’s Compost Bin! features Michi Osato, whose stage name is Sister Selva, wearing a tight gold gown and two neatly woven black braids. During the show, she discards the dress, reveals a fake painted beard and does a reverse striptease that turns her into a hip-hop man, complete with baseball cap. Thus dressed, Sister Selva throws herself into a sexually allusive masculine hip hop routine. She singles out a girl in the crowd – a colleague acting as a clueless audience member – and proceeds to give her a seductive lap-dance. But before touching her, or doing anything sexual and potentially unwanted, she signals the deejay to stop the music. The host, Don Dick Realis, rushes over with a microphone. “Do you consent?” he asks the girl. The girl says yes. The lap-dance resumes. Then, before the act escalates into something resembling explicit intercourse, Sister Selva stops the music again. “Do you consent?” Don DickRealis repeats. The answer is yes again. The action is repeated three or four times, with the music stopping every 30 seconds, until the girl cries out an impatient and enthusiastic “Fuck yeah!” and Sister Selva puts an end to it all by simulating the act of masturbation, and throwing glitter all over the stage as a symbol of her ejaculation.

The issue of enthusiastic consent is one dear to the #MeToo movement and the most contemporary fourth wave feminists. So, where do they stand in this debate? Are they going the anti-pornography way, or the sex-positive way? Or are they taking valid arguments from both sides and putting them together?

Judith Levine, a prominent sex-positive advocate and author of Harmful to Minors: The Perils of Protecting Children from Sex, worries about the strength of the anti-porn movement and its effect on young people.

“We don’t make sex better by just protecting ourselves from danger,” she said in a recent interview. “The danger of sex is at the forefront right now, the idea that sex is all about protecting your boundaries, and one of the reasons is that there have been 40 years of abstinence-only education in this country, which only teaches kids that sex is harmful and scary.”

Nona Willis Aronowitz, a journalist who has written extensively on contemporary feminism and the #MeToo movement, including an opinion piece on the New York Times pointing out that in the midst of all the outrage against bad men, #MeToo could lose a rare public opportunity to make sex better, sees pro-sex feminism as edging ahead. “Ultimately, after the Barnard conference, the feminists who were kind of blanket anti-sex in that particular way won the conversation for decades,” she said. “But since then, anti-pornography has kind of gone out of fashion. The concept of yes mean yes, of affirmative consent, is really pro-sex.”

That said, the #MeToo movement has given a new validation to women’s rage against men which brought the unexpected rehabilitation of prominent figures of the anti-pornography movement of the past, perhaps most notably Andrea Dworkin. As Pulitzer Prize winner Michelle Goldberg wrote in a February 2019 opinion piece for the New York Times, until a few years ago Dworkin was seen mostly as a negative figure. She never actually said “all sex is rape,” a quote that is often attributed to her, but she came close, as when she declared that heterosexual sex is “the pure, sterile, formal expression of men’s contempt for women.” But now, a recent article in The New York Review of Books describes her as “rightfully angry,” journalist Rebecca Traister cites her as one of the inspirations for her own book, Good and Mad, and a pin with her face and the slogan “resist the pricks,” is sold online for $12 as part of a collection honoring important women, including the American rapper Remy Ma, dancer and secret agent Mata Hari, and Shirley Chisholm, the first black woman to be elected in Congress.

Lorna Bracewell, a political scientist at Flagler College in Florida who focuses on feminism and contemporary political thought, sees this development as part of a general re-radicalization of feminist thought. Both sides of the feminist sex wars had their good points, she said in a phone interview, and they were engaging in a revolutionary action acknowledging that “one of the ways in which gender power is exercised is sex.” In her view, whether the #MeToo movement lies more towards the anti-pornography or the pro-sex side of the debate is beyond the point. “Feminism is finally returning to some of the original radicalism that started the sex wars, [but] on both sides,” she said, “and in the #MeToo moment, there is [again] a radical effort to revolutionize sex as a political institution.”

With their cheek and their glitter, their gender bending narrative and their naked bodies, brASS Burlesque’s shows are indeed trying to revolutionize sex as a political institution. The task might be too mighty. But they’re contributing in changing the idea that only certain bodies are good enough to be sexy and admired. And that’s part of the revolution. For many people taking up burlesque in the past years, the attraction comes from the freedom to be sexy, naked and ironic even with bodies traditionally put aside by society, because too big, or too dark, or gender non–conforming.

Cathleen Parra, for example, started doing burlesque because she saw Lillian Bustle’s Ted Talk on sex positivity while working as a photographer focusing on empowering images of women’s bodies. She decided she had to try it immediately and enrolled in the New York School of Burlesque. Now she’s part of the plus-sized burlesque troupe Sister Bear Burlesque, and she occasionally performs with brAss Burlesque. Her stage name is Regal Mortis, “the girl who’ll make you stiff.” Her brASS Burlesque performance is called Man-Eater, and features her wearing a polka dots apron and chewing bloody human parts fished out of a bowl where she mixed an unlikely stew of beans and red wine. But the Man-Eater act is not her favorite one. Her favorite burlesque act is one called “Smooth” and is inspired by her experience of being fetishized as a Latina woman. In it, she comes on stage dancing to the Carlos Santana hit “Smooth.” The act looks like classic burlesque striptease at first. But then, with every piece of clothing removed, she reveals a wound.

“I peel a glove, and all of a sudden a bone is popping out. And I take off my corset, and my ribcage is exposed. And I’m reassuring the audience all the time. Like, it’s fine, no, really, it’s okay. I can keep going.

“Until the end, when I’m like, well, I’ve ripped all my flesh off. I guess I’m going to embrace it.”

Follow Bianca on Twitter